A muddled and confusing attempt at feminist reinvention.

Helen of Troy was “the face that launch’d a thousand ships”, and “burnt the topless towers of Illium”. Most remember the opening line of Marlow’s poem, but it’s the second line That Witch Helen focuses on: how women are blamed for men’s violence.

Blending a mixture of storytelling, Greek myth, and lots of swaying around inside fabrics, Catie Ridewood’s reclamation of an infamous figure is a worthy idea unevenly and, in some moments, embarrassingly explored.

As with a lot of myth, the Greek Heroic Age is a mess of contradictions, nonsense, and eternal reinvention. Ridewood takes Helen’s origin story seriously, aiming for grittiness, which is hard when you’re trying to explain that you were born from an egg when the King of the Gods disguised himself as a swan in order to have sex with your mother.

This clashes with some of the extremely horrific sections of Helen’s mythical story, such as her abduction and probable rape as a child by Theseus, the God-King and hero of early Athens.

Again, Ridewood is making a fair point here – why do we still call these men heroes? Still, the mixture of understandably traumatic backstory and complex Greek myth is a hard one to follow, and the dissonance of both content and tone makes it hard to take seriously.

There have been lots of interesting feminist takes on Greek myth across the centuries; Medea and Helen’s own sister Clytemnestra are, for example, both fascinating figures in their own right and useful ciphers for understanding ancient themes.

Ridewood’s Helen lacks personality by comparison. We’re introduced to an optimistic soul, with fond memories of running wild as a fierce child of the warrior-island of Sparta. Despite a few line stumbles, the audience is, initially, on-board and convinced, as modern song choices (including Bikini Kill’s “Rebel Girl”) are shorthand for the character’s latent power.

The chariot wheels start to fall off when Helen meets Paris, he of “diplomatic mission” to Greece turned sexy suitor. Helen is given agency here in her small domestic world – encouraging her husband, Menelaus, to head off on a jolly so she can seduce this handsome flirty man who has been drinking from her cup during the sweaty and eternal banquets of ancient Greece.

This infatuation is portrayed as slight, even whimsical, and Ridewood’s attempts to divine pathos for Helen’s abandoned daughter Hermione lack impact after the Heat-magazine style cooing over the perfect romantic man.

After their flight back across the Agean to Troy, we’re introduced to Helen’s perspective on one of our oldest stories. We are told of the gathering of the armies against Troy, and a brief, deliberately pathetic depiction of the main men involved, including a Hollywood-style Achilleus and an inexplicably Scouse Odysseus.

This is another jarring element of this production, with Helen and the characters she portrays occasionally reverting to modern vernacular.

The misogyny and callous cruelty of these myths are again laid bare – such as the sacrifice of Agamemnon’s daughter to the Goddess Artemis to ensure a fair wind for the invading Greeks. But with a show that stretches on well beyond the hour mark, a wider or more sophisticated point, or reclamation of Helen as a feminist figure, still seems beyond us.

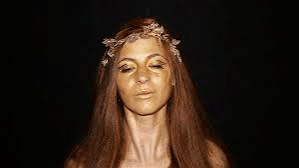

Imagine our surprise, then, when post-Troy Helen – of divine provenance, remember – paints herself gold and becomes some kind of avenging, lean-in, girlboss feminist from beyond the stars, as a recorded voiceover unleashes a terribly cringe mantra: “Diana, we hear you, Monica (Lewinsky?), we hear you… Meghan [Markle], we hear you.”

When the lights go up, it’s a relief to escape.

Leave a comment